What do bioengineers do?

When I ask children to draw a picture of a bioengineer, they usually look at me with a confused expression and say “what is a bioengineer?” A few children might draw a picture of a geeki guy wearing a lab coat (+ hoodie + headphones) and then one or two children may draw a picture of a guy wearing a white bunny suit.

Usually when I tell young people I am a bioengineer, they look at me and say, “oh no, really?”, or “wow, you must be really REALLY clever” . When I told my mum that I had left industry to be a PhD student at the Department of Engineering, she asked me “Why?”

The issue is that most people have no idea what bioengineers do at work.

There is a huge misunderstanding in bioengineering. This is not just about engineering. This is about solving big problems in science and engineering.

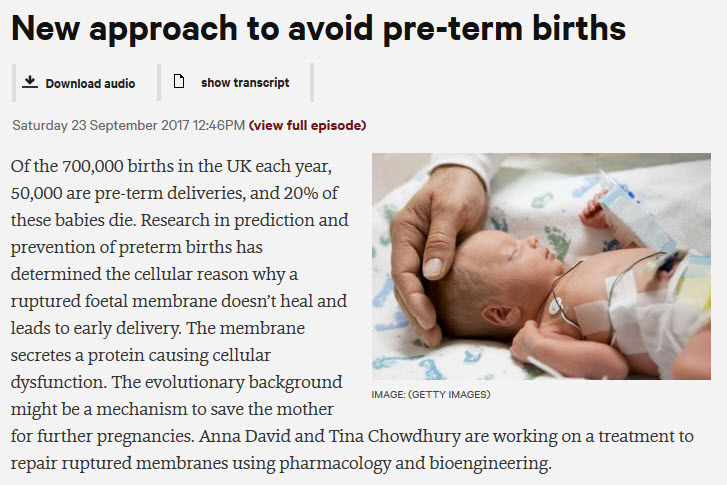

Let me explain to you what I mean by bioengineering. The baby below is very small. She weighs only 700g which is about the weight of an ipad. She was born too early, and if she had been left in the mother’s womb, she would have died. At just 28 weeks of age, we are using technologies in bioengineering to help keep this baby alive.

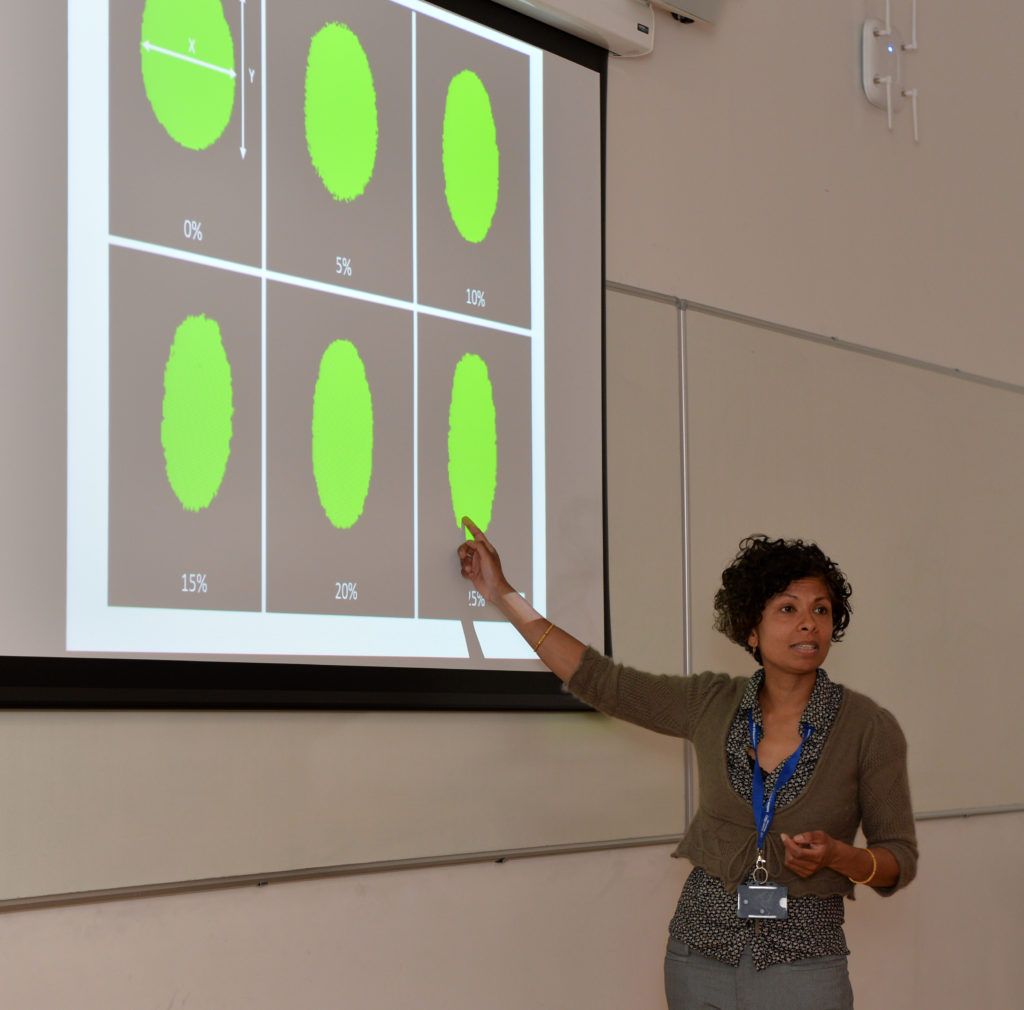

But I am not here to discuss my research. I want to talk about why there are so few women working in bioengineering. We need more women in bioengineering to help the scientists, doctors and engineers make major breakthroughs in healthcare. I may have trained as a scientist, but I am working in a multi-disciplinary environment with engineers, doctors, surgeons and scientists, and together we are developing therapies that could one day help save babies lives.

So, why are there few women in bioengineering? It is about making the right choice. Young people’s choices in education and careers are shaped by peers, parents, their interaction with role models and their individual self-determination.

Even today, the negative stereotypes about girls’ abilities in maths and science persist even though GCSE results for girls are better than boys. In A-level Physics, girls outperform boys. The subjects where boys managed to beat girls are in A-level Welsh, French, German, and Spanish.

There are also clear gender differences in the choice of course at university with cultural, socioeconomic barriers and parents career aspirations influencing choice.

World-wide, there are more women going to university than men. Even though women are more qualified than men (World Bank, UNESCO), they are choosing subjects in nursing and education instead of science and engineering.

If we are going to succeed as a country, we need to train more scientists and train more engineers. This means doubling the number of graduates and apprentices in engineering from 40, 000 to 80, 000 by 2020, otherwise we will not meet demand.

In the UK, only 5% of women are engineers. This is the lowest proportion in the EU. In leadership positions such as science and engineering, women aren’t even getting a foot in the door. We need to close the gender gap if we are going to meet demand and drive economy and growth.

My daughters are learning to be bioengineers. They are age four and nine. Already, at this age, girls loose interest in maths, science and engineering even though they are just as capable as boys. The negative stereotype is learnt early and persists through primary school, secondary school, universities and the workplace. At a very young age, children are confronted by gender stereotypes with girls toys and boys toys, and are influenced by stereotypes about men’s work and women’s work.

I asked my daughter to draw a picture of a bioengineer. Her version is the Disney character from Frozen, with long, golden hair. I am wearing a pink lab coat. She is wearing a blue lab coat. She is Elsa. I could blaim Disney, but we do not have a TV at home. This is peer pressure that is learnt from a very young age and is mirrored in the work place.

Young girls think science and engineering are difficult subjects.

Young girls think science and engineering are for boy’s.

When girls watch tv programmes in science and engineering, they say it looks intimidating and boring.

If we can change this perception early, then we can encourage young girls and help them to realise their potential and possible future in science and engineering.

So how do you encourage girls to like science and engineering? We need to start early. I mean very early. Babies use spatial reasoning right from birth. This is not about eating dinner. This is about play. Learning plays a big role and activities that exercise and nurture spatial skills will improve performance.

For example, every time I walk away from my baby, she notices I look smaller and If I move even further away, she responds (cries). This ability continues to develop until around age 10. She will learn concepts about space, such as near and far, which provides a foundation for spatial awareness and visual spatial attentions later in life.

Researchers say that the quality and quantity of play is especially important in spatial thinking in children. Children who have good spatial skills are strong in engineering and science.

So how can we help to develop spatial skills at a young age?

This is not just about working hard. If we want to improve spatial skills, then training matters.

Baby boys build and by the time they are toddlers they are playing video games. This play helps boys to practice mental rotation and boost spatial skills.

In adults, there is good evidence that practicing mental rotation and visual attention can boost spatial skills.

For example, Jing Feng and colleagues in Toronoto (2008) found that undergraduates improved visual attention and mental rotation skills after only ten hours of playing an action video game.

Women can match men when learning spatial skills.

All it takes is a bit of brain training.

If we want to encourage more girls into science and engineering, we need to start early, when they are babies, and show them how throughout childhood, schools, universities and the workplace.

We need to mentor and teach children that intellectual and spatial skills can be acquired. This encourages the child to learn more, embrace challenges, learn from criticism and be inspired by others’ success. We need to send the message that you can value growth and learning. There is a need to recognise that women should be encouraged and helped to realise their potential and possible future in science and engineering.

The more we can help young people and support engagement with bioengineering, the better for us and our future global leaders.